|

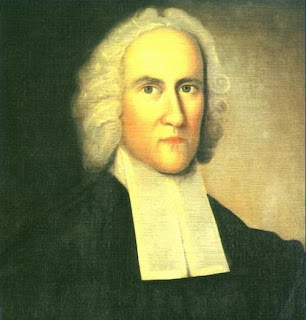

| Jonathan Edwards wrote in defense of slavery |

In this series of articles on racism and slavery in Puritan New England, we have seen that Puritans often treated their Black and Native American neighbors as sub-human. For example, New England law permitted Puritans to abuse their slaves even if it led to their deaths, as we saw was the case with the puritan minister, Stephen Williams, who drove enslaved Africans to take their lives within days of beating them without pity.

Though most Puritans were kind to their slaves, New England law allowed African Americans to be treated in dehumanizing ways, including making it possible for masters to separate husbands and wives or to remove children from parents for economic gain.

Our previous article in this series looked at the relationship of the Great Awakening to the question of slavery in the churches of New England. This article continues that discussion by looking specifically at the views of Jonathan Edwards on slavery. (For a brief biography of Jonathan Edwards, see my article 'Jonathan Edwards" God's Melancholy Saint')

Though most Puritans were kind to their slaves, New England law allowed African Americans to be treated in dehumanizing ways, including making it possible for masters to separate husbands and wives or to remove children from parents for economic gain.

Our previous article in this series looked at the relationship of the Great Awakening to the question of slavery in the churches of New England. This article continues that discussion by looking specifically at the views of Jonathan Edwards on slavery. (For a brief biography of Jonathan Edwards, see my article 'Jonathan Edwards" God's Melancholy Saint')

In the revivals he initiated, Edwards was adamant in declaring spiritual liberty to Negros. In his 1737 Faithful Narrative, Edwards recalled with pride how “Ethiopia has stretched out her hand; some poor Negroes have, I trust, been vindicated into the glorious liberty of the children of God.” He made similar remarks in his 1743 publication Some Thoughts Concerning the Revival. Yet Edwards was careful to insist that this “glorious liberty” always remained a purely spiritual phenomenon and that the equality enjoyed within the walls of the church between people with different skin colour remained the province of the immaterial realm, lacking concrete social embodiment.

Church records show that African Americans were baptized and admitted into church membership long before the revivals of the 1730s and 1740s, though the eighteenth-century revivals did act as a catalyst for bringing increasing percentages of blacks into Christian fellowship. Edwards’ own Northampton congregation saw nine African slaves received into church membership between the years 1729 and 1740, all but three of which had entered when the revival was at its height in 1734/5. In other regions, converted slaves seem to have been enlisted in the work of spreading the revival to others, for one of the criticisms of the revivals made by “old lights” like the Boston Congregationalist minister Charles Chauncy (1705–1787) was that uneducated blacks were doing “the Business of Preachers.”

Edwards responded to these types of criticisms by insisting that God does not discriminate when giving the gospel, and he appealed to passages such as Galatians 3:28 to show that God offered salvation to both slaves and free. Yet this non-discriminatory stance seems to have limited itself to the spiritual realm. While unapologetically asserting the spiritual equality of all believers, regardless of skin colour, he simultaneously supported and even participated in an institution that enabled one group of Christians to break up the families and marriages of another group, solely on the basis of their skin color.

By maintaining a strict dualism Edwards between the material and the immaterial, Edwards could offer African Americans the dignity of being fellow citizens of the Kingdom of God and co-heirs in Christ while simultaneously defending an institution which treated them as mere property. This irony was hinted at by Kenneth Minkema, in his article ‘Jonathan Edwards's Defense of Slavery’ for The Massachusetts Historical Review:

By maintaining a strict dualism Edwards between the material and the immaterial, Edwards could offer African Americans the dignity of being fellow citizens of the Kingdom of God and co-heirs in Christ while simultaneously defending an institution which treated them as mere property. This irony was hinted at by Kenneth Minkema, in his article ‘Jonathan Edwards's Defense of Slavery’ for The Massachusetts Historical Review:

In his published treatises on revivals, Edwards time and again pointed to black converts who, he declared, had been “vindicated into the glorious liberty of the children of God.” The “liberty” he assumed for blacks was not a social and political liberty on a par with whites, but a solely spiritual one. Even ontologically, Edwards harbored a typically paternalistic outlook that saw black and Indian adults, before conversion, as little more than children in the extent of their innate capacities. To be sure, both blacks and whites were equally in need of the means of grace and of salvation, but that was as far as equality went. Edwards and his fellow colonists lived in a hierarchical world, including racially, and that hierarchy was to be strictly observed…”

While this racial hierarchy tended to be unquestionably accepted throughout Puritan New England, by the time of Edwards there may have begun to be what Minkema has described as “a vein of antislavery sentiment that bubbled just below the surface of New England society.” Evidence for this comes from the case of Reverend Benjamin Doolittle, a Yale graduate who settled in Northfield 1718, along what is now the northern border of Massachusetts. Doolittle, who also worked as a doctor and a proprietor's clerk, aroused some dissention among his flock for allegedly living in indulgence, yet quibbled with his flock over the payments of firewood to which he was entitled. Believing their pastor to be avaricious and acquisitive, members of the Northfield congregation organized charges against Dootlittle, and it is interesting that one of the complaints was that he owned slaves. Whether the indignation at their pastor’s slave owning had an ethical basis, or was taken to be merely one more example of his luxurious lifestyle, we will never know. It may even be that the complaint about the slave-owning was motivated by racist fears that were becoming increasingly prevalent because of the growing population of blacks in North America. Whatever the reason for this controversy may have been, Edwards was asked to prepare a letter or address defending Doolittle’s right to own slaves. The request came only a few weeks after Edwards delivered his iconic sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. While the notes of the document only exist in draft form, they give remarkable us insight into Edwards’ views on the subject.

What is interesting about Edwards’ notes is that while he unhesitatingly defended slavery in North America, he was equally adamant in condemning both the slave trade and abusive masters. He acknowledged that the slave trade was “cruel” and denied that “nations have any power or business to disfranchise all the nations of Africa.” At the same time, he defended the institution of slavery by appealing to examples of permissible slave-owning in scripture. Edwards also followed general Puritan thinking in appealing to divine sovereignty: “’Tis he that makes ‘em to differ in their birth and circumstances of life.”

Edwards’ opposition to the overseas slave trade didn’t stop him from directly participating in race-based slavery at home, even though the latter helped to support and sustain the former. In 1731, he travelled to the harbour town of Newport, Rhode Island for the purpose of purchasing a slave girl. This town was well known as a port for the transatlantic slave trade and a point of destination for those who wished to attend the slave auctions. During his time in Newport Edwards paid Richard Perkins (the commander of a slave ship) eighty pounds for an African girl named Venus, who was around fourteen years of age.

This would not be the last time the family participated in the trade of human flesh. In 1746, Edwards arranged for his friend Robert Abercrombie, to purchase a slave woman to help Sarah with the domestic work. Eight years later Edwards informed his friend Bellamy that they were interested in purchasing his “Negro woman.” Three years after that he ended a letter to his daughter, Esther Edwards Burr, by expressing a wish to purchase the Burr’s slave Harry. Edwards was not alone in these activities. Minkema reminds us that “Sarah, who as regulator of the domestic sphere was probably more directly concerned in the daily oversight of the family slaves than Jonathan, aggressively searched out potential slaves, which shows that women could take an active hand in the slave market.”

This would not be the last time the family participated in the trade of human flesh. In 1746, Edwards arranged for his friend Robert Abercrombie, to purchase a slave woman to help Sarah with the domestic work. Eight years later Edwards informed his friend Bellamy that they were interested in purchasing his “Negro woman.” Three years after that he ended a letter to his daughter, Esther Edwards Burr, by expressing a wish to purchase the Burr’s slave Harry. Edwards was not alone in these activities. Minkema reminds us that “Sarah, who as regulator of the domestic sphere was probably more directly concerned in the daily oversight of the family slaves than Jonathan, aggressively searched out potential slaves, which shows that women could take an active hand in the slave market.”

When Sarah died in 1759, six months after her husband’s abrupt death, she did not leave behind instructions for her married slaves, Joseph and Sue, to be freed, as some Puritans were in the habit of doing in their last will and testament. Rather, she left instructions for them to be sold in the market where future owners would have the right to separate the couple. The money was to be divided among her children.

Edwards’ actions with respect to African Americans suggest a strong tension between the spiritual and the social which we have already seen remained a general feature of Puritan thinking towards African Americans. His eagerness to bring salvation to Africans and to upgrade the dignity they enjoyed within the walls of the church ran parallel with a defence of the institution of race-based slavery and a willingness to treat blacks as property for the sake of his family’s financial profit. These blind spots were not the inevitable result of Edwards cultural context, for there were and had been voices opposing the slave trade within both the Puritan and evangelical traditions. The English Puritan Richard Baxter (1615–1691) had a holistic vision that led him to speak out against both slavery and the slave trade while John Wesley was a staunch opponent of the institution.

George Whitefield

Jonathan Edwards' partner in revival, George Whitefield (who I have written a brief biography about here),

Whitefield’s evangelistic efforts contained a strong social justice dimension, as evidenced most clearly in his Georgia orphanage project. Nevertheless, the dualism he entertained throughout his life between the sacred and secular ensured that there would be significant gaps in his approach to social reform. One such gap was his approach to the institution of race-based slavery.

Few people worked as hard as Whitefield to advocate the evangelism of slaves. Whitefield was prepared to alienate Anglican authorities in the South through his insistence that slaves had souls that could be evangelized, while he prompted widespread controversy in Philadelphia after a sermon in which he argued that black people have souls. He cared deeply for the slaves, attempted to start a school in Pennsylvania for blacks, and made the salvation of African slaves a foremost concern during his American visits. Despite this concern for their spiritual condition, Whitefield showed a degree of cognitive dissonance when it came to the material condition of African Americans.

Like many of his contemporaries, Whitefield appealed to the spiritual benefits available to blacks in order to justify their material enslavement. Kenneth Minkema reminds us that Whitefield “admitted that slavery was a ‘trade not to be approved of’ and preached the doctrine of Christian freedom, for which he came under attack after the New York ‘revolt.’ Nonetheless, he condoned slavery and justified his position by emphasizing the religious benefits that slaves could enjoy, assuming they had conscientious and charitable masters.”

Whitefield went out of his way to repudiate Wesley’s denunciation of slavery in Georgia, urged the legalization of raced-based slavery in the state and even bought slaves for himself. His anonymous 1743 epistle A Letter to the Negroes Lately Converted to Christ in America, reflected what Stephen Stein has called “an astonishing insensitivity to the human rights of slaves by way of contrast with his firm conviction about the property rights of slaveholders.” Stein continued:

“The good life for the blacks, according to the Grand Itinerant, was a spiritual reality. ...Whitefield propped the institution of slavery with evangelical braces. Here he provided religious sanctions for the developing racial patterns in the south during the colonial period. Whitefield used certain traditional tenets of Protestantism to exalt the peculiar institution above the value of human life. He urged blacks to die rather than disobey, for in so doing they were fulfilling the injunctions of the gospel.”

The concern to save the souls of African Americans but not their bodies, to bring religious equality to the slaves while abusing their bodies, and to defend the institution of race-based slavery on the grounds that it offered significant religious benefits, suggests a failure to fully integrate the material and the spiritual, the sacred and the secular, the visible and the invisible, the religious and the social.

Further Reading

- Racism and Slavery in Puritan New England (Part 1)

- Racism and Slavery in Puritan New England (Part 2)

- Racism and Slavery in Puritan New England (Part 3)

- Were the Puritans Racist?

- Precious Puritans (Part 1)

- Precious Puritans (Part 2)

- A pdf of all 4 blog posts with references fully documenting every claim

- List of my anti-racism articles

Some of this material will be appearing in the monthly newsletter of Christian Voice, a ministry whose website is http://www.christianvoice.org.uk/. It is printed here with permission of Christian Voice.

____________

Read my columns at the Charles Colson Center

Read my writings at Alfred the Great Society

To join my mailing list, send a blank email to robin (at sign) atgsociety.com with “Blog Me” in the subject heading.

Click Here to friend-request me on Facebook and get news feeds every time new articles are added to this blog.

1 comment:

Thank you for your research. It is good to know these things, however disappointing they are.

Post a Comment